Grand Teton

13,775 - Wyoming

Summit Pen Company Iconic American Peaks > Grand Teton

Grand Teton - An Iconic American Peak and part of the Summit Pen Company Iconic American Peaks Collection

The Grand Teton has captured the imaginations of generations of climbers. With roughly 90 routes and variations to its summit, Grand Teton offers a wide range of experiences for all levels. The highest peak in the Teton Range, the Grand Teton can be summited via routes that receive a low fifth class grade all the way up to highly technical aid, free and mixed routes. Exploration of the Grand has been accomplished thanks to the vision and boldness of many waves of climbers, each group seeing new possibilities and pushing the boundaries of the last.

The Grand Teton has captured the imaginations of generations of climbers. With roughly 90 routes and variations to its summit, Grand Teton offers a wide range of experiences for all levels. The highest peak in the Teton Range, the Grand Teton can be summited via routes that receive a low fifth class grade all the way up to highly technical aid, free and mixed routes. Exploration of the Grand has been accomplished thanks to the vision and boldness of many waves of climbers, each group seeing new possibilities and pushing the boundaries of the last.

It is tempting upon reading the accounts of early Grand Teton ascents to write off the mountain's early pioneers as greenhorns. In truth, the men and women who made the first ascents of the mountain were the most visionary of all, daring to believe they could reach the summit when most others thought it was impossible. Encountering new and unknown terrain, and without modern technical skills or equipment, these adventurers found a true test of their stamina and resolve on the Grand Teton. It is their legacy that has allowed countless other climbers to believe they are capable of reaching the summit, and to explore new and more daring routes.

With little chance of finding uncharted terrain on the Grand Teton today, contemporary climbers still face a significant challenge in climbing the Grand Teton. Any climber who attempts the Grand Teton exposes themselves to objective hazards and risks, such as rock fall and lightning. And each climber also faces the challenge of overcoming fears and doubts, of pushing their bodies beyond perceived limits to reach the summit. Continuing with a long tradition of climbing the majestic Grand Teton, climbers today test their courage and tenacity each time they attempt the Grand.

With little chance of finding uncharted terrain on the Grand Teton today, contemporary climbers still face a significant challenge in climbing the Grand Teton. Any climber who attempts the Grand Teton exposes themselves to objective hazards and risks, such as rock fall and lightning. And each climber also faces the challenge of overcoming fears and doubts, of pushing their bodies beyond perceived limits to reach the summit. Continuing with a long tradition of climbing the majestic Grand Teton, climbers today test their courage and tenacity each time they attempt the Grand.

The Grand Teton pen is a symbol of the mountain's climbing history, celebrating the vision and success of climbers for 150 years. Climbers today can be proud to climb in the footsteps of climbing greats who have tested themselves on the Grand Teton. The Grand Teton pen reminds us of our connection to the long and storied climbing history on the peak, and connects us to the basic commonality all climbers have: to seek challenge; to encounter doubt, exhaustion, and frustration; and to succeed in the face of these challenges. To test oneself in the wilderness and against the elements brings us to our most basic, true selves. We emerge from these experiences with great clarity and new confidence our capabilities.

Grand Teton History

Much about the early history of the Grand Teton is debatable. The mountain's name, for example, is attributed to various sources. Some say the Grand Teton is named for the Teton Sioux tribe. Others reference the name given the Tetons by French fur trappers, "Les Trois Tetons" or "The Three Breasts", with the Grand Teton meaning "large teat". Or perhaps it is a shortening of the name given the mountain by the Shoshoni people: they referred to the Teton range as the Teewinot, a word that means "many pinnacles", and the name they used for the Grand Teton itself meant "hoary headed fathers". Dr. Ferdinand Hayden's expedition, the first group to claim the summit, attempted to rename the peak Mount Hayden but the name didn't stick.

Perhaps one reason the name Mount Hayden was not adopted was due to the general controversy over whether Hayden's team even reached the summit of the Grand Teton. Today, the general consensus is that this early party reached the summit of The Enclosure, a subsidiary peak of the Grand Teton. A rock structure which gives the mountain its name, The Enclosure, was evidence that native people had been to this summit prior to Nathaniel Langford and James Stevenson on Hayden's team.

When William Owen reached the summit of the Grand Teton in 1898, he found no evidence that anyone had been there before. He strongly believed that the account given by Langford and Stevenson matched the climb to The Enclosure's summit, not the Grand Teton. He vehemently asserted himself as the first to reach the mountain's summit, going so far as to purchase a plaque that was placed at the summit proclaiming his feat.

Whether Langford and Stevenson reached the summit of the Grand Teton or not, their 1872 climb made the summit seem attainable to future climbers. They had the vision and courage to climb through the unknown, and they blazed the trail for climbers to come. It is difficult today to relate to the degree of mystery and challenge those early climbers faced. Their written account of the ascent gives a sense of their experience.

Whether Langford and Stevenson reached the summit of the Grand Teton or not, their 1872 climb made the summit seem attainable to future climbers. They had the vision and courage to climb through the unknown, and they blazed the trail for climbers to come. It is difficult today to relate to the degree of mystery and challenge those early climbers faced. Their written account of the ascent gives a sense of their experience.

Even the approach to the climb was harrowing. It was 11 degrees Fahrenheit when the team of fourteen adventurers set out with their alpenstocks (a precursor to the ice axe, an alpenstock or "alpine stock" is essentially a walking stick with an iron point on the end) and a bacon sandwich each. They encountered ravines, boulder fields, a snowfield they described as resembling frozen waves in an ocean, a ridge of crumbling rock, an iced-over lake, and a steep snow field on their way to the base of the Grand Teton. Without a trail to follow or a sense of the distance, the team was close to turning back before they even reached the base of the peak. Langford wrote of their extensive approach: "Still receding and receding those lofty peaks seemed to move before us like the Israelites pillar of cloud and had we not seen this last snow field actually creeping up to the top and into the recesses of that lofty crest from which the peaks shoot upward to the heavens we should most willingly have turned our faces campward from the present point of vision and written over the whole expedition: Impossible."

Continuing onward, the group reached the saddle below the Grand Teton. "We ate part of our luncheon while upon The Saddle which we reached about noon and rested there a quarter of an hour beneath the shadow of the Great Teton. It seemed as we looked up its erect sides to challenge us to attempt its ascent." Taking the challenge, a portion of the group ventured into more vertical terrain. Langford describes the fourth and easy fifth class climbing in dramatic detail: "We found ourselves clambering around projecting ledges of perpendicular rocks, inserting our fingers into crevices so far beyond us that we reached them with difficulty, and poising our weight upon shelves not exceeding two inches in width, jutting from the precipitous walls of gorges from fifty to three hundred feet in depth. This toilsome process …severely tested our nerves."

While most groups today do rope up for sections of this climb, the route the group was taking is one of the least technical paths to the summit. However, because the terrain was completely unknown and the climbers were not aware that anyone had ever reached the summit before, their level of anxiety was high. Langford wrote about one moment of particular worry as he watched another member of his party: "I saw him fall and supposed he would be dashed to pieces. A moment afterwards he crawled from the friendly snow heap and rejoined us unharmed and we all united in a round of laughter as thankful as it was hearty. This did not quiet that tremulousness of the nerves of which extreme and sudden danger is so frequent a cause and underlying our joy there was still a feeling of terror which we could not shake off." There was a definite sense among the party that they might die in their attempt to reach the summit of the Grand Teton.

Whether they climbed the Grand Teton or The Enclosure, Langford and Stevenson reached the summit by the skin of their teeth. Langford describes their final frenzied push to the summit: "Capt. S and the writer made one more attempt to scale the rock confronting us. A rope which the writer had brought with him proved of great service now, and throwing it over a slight projection above our heads, the writer, supported and steadied as well as hoisted by Capt. Stevenson below, drew himself up till he could firmly plant his fingers in a crevice in the flat surface of the rock; and then, with his feet supported by Capt. S's shoulder, clambered to the top. Capt. S preferred to trust himself to his staff rather than the rope. I thrust one end down to him, which he, with this aid, grasped firmly and climbed to the top." This sort of climbing – utilizing the items the climbers had with them to make an ascent possible by any means – would continue for some time on the Grand. Lacking the modern equipment climbers rely upon today to aid us in our efforts and keep us safe such as climbing shoes, ropes, or artificial protection, these early pioneers made do – and in so doing, they made history.

Each time a peak such as the Grand Teton is climbed, the weather and conditions are different. For this reason, the difficulty of a particular route can vary greatly. Should ice or water be present, a route may prove much more difficult than without. In his report of the climb, Hayden noted that the presence of migrating grasshoppers also contributed to the group's successful ascent. Apparently, grasshoppers became frozen above the peak and fell; their carcasses littered the snowfields. Hayden believed the grasshoppers provided traction for the climbers on otherwise slick terrain. The presence of the grasshoppers may well have made the route possible for these climbers.

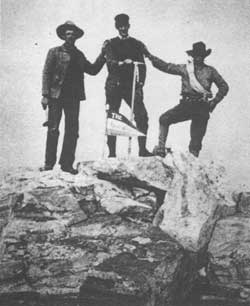

The first undisputed ascent of the Grand Teton was on August 11, 1898. A group of four sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Club of Denver - Franklin Spalding, William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, and John Shive – set out to repeat the Hayden expedition's route. Spalding's team had the same doubts and worries as they climbed as the team nearly twenty years before described. And they faced similar hazards along the way. At one point the group had a narrow miss with rock fall: one of the falling rocks came as close as to brush one climber's hat.

The first undisputed ascent of the Grand Teton was on August 11, 1898. A group of four sponsored by the Rocky Mountain Club of Denver - Franklin Spalding, William O. Owen, Frank Petersen, and John Shive – set out to repeat the Hayden expedition's route. Spalding's team had the same doubts and worries as they climbed as the team nearly twenty years before described. And they faced similar hazards along the way. At one point the group had a narrow miss with rock fall: one of the falling rocks came as close as to brush one climber's hat.

Spalding and Owen both reached the summit of the Grand Teton and they were to surprised to find no cairn or other mark to indicate humans had been there before them. Furthermore, the description of the route recorded by Hayden's team did not match the challenges Spalding and the other climbers encountered near the summit. They came to believe that Hayden's group had not actually ascended the Grand Teton but the lesser mountain known as The Enclosure.

Owen described the final portion of what has come to be known as the Owen-Spalding route in great detail: "The consciousness that a fall would land us 3000 feet below gave us a decidedly creepy sensation. We had to dig our fingers in the rough granite in places to pull ourselves along. We encouraged each other by keeping up a natural conversation, but it was with an inward feeling of relief that we left the ledge and came to a sort of niche with a small overhanging rock. Over this we threw a rope — an action that required a cool and steady hand and a keen eye. We pulled ourselves up and out over this 3000 feet of space and continued up on the niche to about 50 feet. It was so narrow that we had to use our feet, elbows and knees. All of the rock was slippery and we could not go too carefully. When we reached the top we went on another gallery for a distance of nearly 200 feet to the west; then up another ice niche, in which we were forced to cut five steps. It was sixty feet high and led on to a ridge. We followed a snow ridge for 200 feet, and then over the sharp, jagged, eruptive rocks, so noticeable above the timber-line, clambered with a shout to the top. We had been climbing for eleven hours. It was a grand sight, one of the grandest on earth."

The Owen-Spaulding route has become such a popular and indeed legendary route that various sections of the route have been named. The names, which have the air of myth, include The Eye of the Needle, The Belly Roll, The World's Best Handhold, and The Crawl.

Again, it was many years before another party attempted to climb the Grand Teton. Late in August 1923, Albert Ellingwood and Eleanor Davis were camped near the base of the mountain, scouting a probable route to the summit, when three college students from the University of Montana showed up to attempt the peak. Never having laid eyes on the Tetons before, Dave DLap, Quin Blackburn and Andy DePirro had seen the mountain on a map and decided on a lark to attempt the summit before the fall semester started. They had no mountain climbing experience or any gear, just tenacity and good luck.

The unlikely trio drove a Model T truck to the area and came across Ellingwood who directed them toward the saddle below the peak. There was no trail yet to the saddle, and the three had to bushwhack their way to the base of the mountain – they covered 7,000 vertical feet in their single day ascent of the Owen-Spalding route. They picked a route that led them to the base of the Owen Chimney, which was covered in treacherous ice. Without crampons or ice axes, they formed a human ladder and got Blackburn up the chimney. DePirro was partway up, wedged into a crack, and DLap was still down below. Showing a lack of pretense and a stroke of resourcefulness, DePirro took off his pants and lowered a leg to DLap. Hanging onto the pant leg, DLap was to climb over the overhang and join the other two. They made the summit and then descended safely.

Just two days later, Ellingwood and Davis also climbed the Grand Teton via the Owen-Spaulding, Davis making her mark as the first woman on the summit. The second female ascent was made by Geraldine Lucas the following year; unlike Davis, who was a respected mountaineer, Lucas was a 59-year-old Jackson Hole local. In the following years, the Owen-Spaulding route was repeated many times, most notably by legendary Teton Guide Paul Petzoldt. In 1924, at the age of 16, he summited the Grand Teton in a pair of cowboy boots, carrying nothing but a can of beans, a patchwork quilt, and a pocket knife he used to cut steps. Phil Smith and Fritiof Fryxell made many early first ascents in the range. After Grand Teton National Park was established in 1929, the two became the park's first rangers, making their mark by establishing summit registries and carefully recording the area's climbing history.

It was not until 1929 that climbers were successful in establishing another route up the Grand Teton. The East Ridge (III 5.7) was pioneered by Harvard philosophy professor Robert Underhill and his climbing partner Kenneth Henderson. Underhill returned to establish many new routes in the Tetons in the following summers, most notably the North Ridge (IV 5.8) in 1931, a route that is today considered one of the great early American rock climbs. That same year, Glenn Exum established the Exum Ridge Route (II 5.5), now the most climbed route on the mountain. He soloed the route in borrowed football cleats two sizes too big. Together with Petzoldt, Exum organized a guiding service that would grow into Exum Mountain Guides. Exum Mountain Guides has been guiding clients in the Tetons for eighty years.

1931 signaled the beginning of an intensive period of first ascents of peaks throughout the range. In fact, all the major peaks in the area were climbed in 1931 or shortly thereafter. From 1935 on, climbers moved on to establishing new routes up the various peaks or seeking out other challenges. One such undertaking was the first winter ascent of the Grand, completed in 1935 by Paul Petzoldt, his brother Eldon, and Fred Brown. Thanks to a temperature inversion, the team enjoyed warmed temperatures at the Grand Teton's summit than the –20°F recorded in town that day. Jack Durrance was another important character in the pioneering of the Grand Teton. Together with the Petzoldts, Durrance established several difficult routes that pushed the standards of the time.

1931 signaled the beginning of an intensive period of first ascents of peaks throughout the range. In fact, all the major peaks in the area were climbed in 1931 or shortly thereafter. From 1935 on, climbers moved on to establishing new routes up the various peaks or seeking out other challenges. One such undertaking was the first winter ascent of the Grand, completed in 1935 by Paul Petzoldt, his brother Eldon, and Fred Brown. Thanks to a temperature inversion, the team enjoyed warmed temperatures at the Grand Teton's summit than the –20°F recorded in town that day. Jack Durrance was another important character in the pioneering of the Grand Teton. Together with the Petzoldts, Durrance established several difficult routes that pushed the standards of the time.

The great momentum of the 30s in the Tetons was not lost to the war, but just put temporarily on hold. Between 1942 and 1945, very few mountaineers ventured to the Tetons. Most climbers enlisted in the service, many serving as mountain troops. If anything, climbers returned from the war with more gusto and daring than ever before. Routes that had been deemed impossible were climbed, and the numbers of mountaineers in the Tetons greatly increased.

The advances made by climbers in the post-war years opened the door for even greater creativity, boldness and vision. In the decade spanning 1955 – 1965, aid climbing was born, allowing climbers to develop technical skills that greatly increased their potential for establishing new routes. Climbers sought out new and challenging terrain on smaller walls and lesser peaks. Fred Beckey, Yvon Chouinard, Royal Robbins, and Willi Unsoeld, among many others, pioneered new routes during that era. Since that time, advances have been made in freeing aid routes and establishing mixed routes and more pure rock free routes. The late 70s saw a major increase in pure rock climbing routes, and it was at this time that some of the hardest rock routes were established in the Tetons.  The 1980s ushered in hard ice and mixed lines, as climbers attempted technical routes in colder conditions. Climbers have competed for years over the speed record for climbing the Grand Teton. The record is currently held by Andy Anderson who climbed from the Lupine Meadows to the summit and then descended in 2:53:02 on August 22, 2012. Recent years have seen the establishment of some of the hardest routes on the mountain including Golden Pillar (V 5.12) established by Greg Collins and Hans Johnstone in 2003, and Squeeze Box (IV M7 A0), climbed by Johnstone and Stephen Koch in 2007.

The 1980s ushered in hard ice and mixed lines, as climbers attempted technical routes in colder conditions. Climbers have competed for years over the speed record for climbing the Grand Teton. The record is currently held by Andy Anderson who climbed from the Lupine Meadows to the summit and then descended in 2:53:02 on August 22, 2012. Recent years have seen the establishment of some of the hardest routes on the mountain including Golden Pillar (V 5.12) established by Greg Collins and Hans Johnstone in 2003, and Squeeze Box (IV M7 A0), climbed by Johnstone and Stephen Koch in 2007.

Today, a select few climbers continue to find new ways to push the envelope on the Grand Teton and throughout the range, attempting feats past generations deemed impossible. Thousands of rock climbers, ice climbers and mountaineers test their personal limits on the Grand Teton's dozens of established routes and variations. Three of the mountains most popular routes – the Direct Exum Ridge Route, the North Ridge and the North Face with Direct Finish are included in the book "Fifty Classic Climbs of North America"; the Grand Teton is the only mountain to feature three climbs in the book. Two guide services – Exum Mountain Guides and Jackson Hole Mountain Guides – provide professional guides for routes on the Grand Teton and throughout the range to climbers of all abilities from around the world. The tenacity and daring of the peak's earliest pioneers has inspired generations of climbers to see possibility in the seemingly impossible – on the mountain and in ourselves. Climbers journey from around the globe simply to become a part of the Grand Teton's inspiring history.